New cars hit the road with innovations from electric racetrack

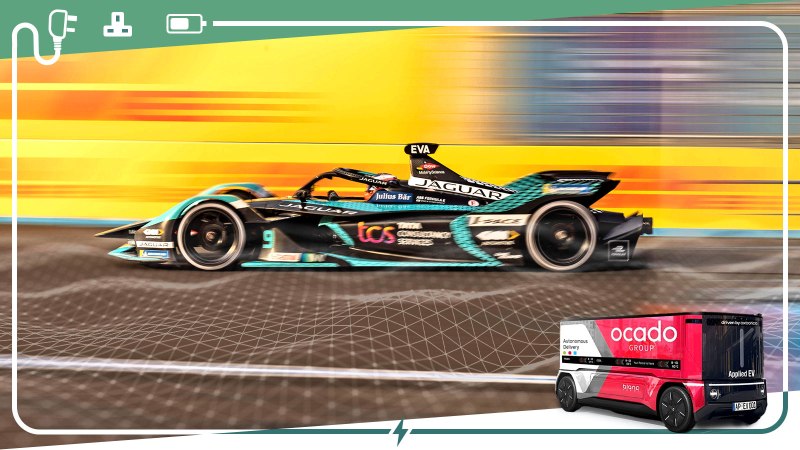

If you own a Jaguar i-Pace electric car, the next update to its on-board computer is likely to have been born on the racetrack. Data from the carmaker’s Formula E electric motor racing team is making tweaks to improve the road car’s performance.

According to James Barclay, the team principal of Jaguar TCS Racing, “software in Formula E is like aerodynamics in Formula One. We update the computer code in our cars race-by-race to eke out more efficiency. It teaches us how far we can safely push the components.” Years ago Formula One boasted of its racing breakthroughs improving road cars; today, as the sun sets on the internal combustion engine, Barclay says the race-to-road contribution from electric motor sport is only just starting.

• Is UK running out of road on its electric ambitions?

Jaguar TCS is part of a cluster of nearly 4,000 engineering, technology and components companies linked to racing and the wider automotive market that are based in Oxfordshire and its adjoining counties. The cluster’s roots lie in the days when Britain was a motor manufacturing powerhouse, but its continuing relevance is a result of the area being the home of global motor sport and of racing research and development.

Most Formula One and Formula E teams are based in the region, known as Motorsport Valley, but that barely scratches the surface of the array of engineering and technology players in the cluster. They have been joined, for example, by experts in connected and autonomous vehicles. StreetDrone has produced a driverless lorry for Nissan; Oxa is doing similar things for Ocado, the online retailer.

Yet the transition to an era of hybrid and all-electric vehicles has upended some old certainties. Companies need new investment and new skills and there’s more global competition. Big manufacturers want specialist suppliers in automotive electronics and software, not widget makers.

“We’re at a crossroads as our industry and customers decarbonise,” Iain Roche, chief executive of the advanced technology division of Prodrive, a Banbury-based racing and engineering company, said. The “recent explosion of different technologies” meant only the most agile and entrepreneurial firms would remain, he said.

Companies that started in electric racing early on are reaping rewards. In 2022, mining giant Fortescue bought Williams Advanced Engineering, which has supplied batteries for Formula E teams since the series began in 2014-15 and has its origins in the Williams Formula One team.

Now called Fortescue WAE, the company is supplying batteries for the mining firm to switch its fleet of vast diesel vehicles to fully electric ones. There will also be an ultra-fast charging system based on its racing circuit technology — but then mining trucks and racing cars have things in common. “Both operate under very harsh conditions: heat, vibration, dust,” said Judith Judson, CEO of Fortescue WAE.

Fortescue bought the business to exploit the technology and take it global. For example, there is a train at a Fortescue iron ore mine in Australia that descends downhill to a shipping port, recharging the battery from the gravitational pull along the way so that it’s ready for the return journey. “All that racing technology now has an industrial application,” Judson said, adding that rail operators were showing interest in the technology.

Xtrac has stayed rooted in motor sport and performance cars. It began making gearboxes 40 years ago and employs 500 people in Britain and America producing hybrid and electric transmissions — getting power to the wheels. The company brought in private equity investors in 2017 and again last year to expand its operations.

“Fifteen years ago it was just gearboxes for petrol and diesel cars. Now it’s many technologies,” Adrian Moore, Xtrac’s chief executive, said. Last year the company designed gearbox parts for the California-made Czinger, a $2 million hypercar that is 3-D printed. “It’s cutting-edge, groundbreaking. Designed here, printed in Los Angeles.”

He is confident that Motorsport Valley will survive because there is no other place with such a critical mass of talent. Most of Xtrac’s supply chain is within about 30 miles of its headquarters in Berkshire. There are automotive clusters in the United States and in “Motor Valley” in Italy, based around Ferrari, Lamborghini and Pagani, “but Motorsport Valley is unique”.

It helps that the government in Westminster recognises that a truly successful mass-market electric vehicle and battery industry will need a thriving technology and component sector further down the supply chain. In recent years, the region has received hundreds of millions of pounds in innovation funding and research grants to work on net zero transport projects.

Prodrive’s heaving trophy cabinet is testament to it being arguably the most successful name in motor racing. Now one of its key skills is integrating electric car technology into the vehicles of the future. Volta Trucks used the firm to develop a fully electric 16-tonne lorry. This year Prodrive will unveil its concept for a “last mile” vehicle, small delivery vans that will be needed if the explosion of ecommerce means consumers want everything on their doorsteps. The vehicle was given government aid.

Roche said such projects underlined the breadth of opportunities for the supply chain, but he worries that a skills shortage could constrain growth. As software and electronics became more important in electric vehicles, the global competition for talent intensified. “Tesla is almost a software company making cars, rather than a car company installing software,” he said.

Mark Preston, the founder of StreetDrone and a former Formula One engineer at McLaren and Super Aguri Honda, said the allure of motor sport would always attract skills. “It’s a proving ground. My experience of Honda is they would send in all their young engineers to do the impossible. By the time they’d finished, they knew anything was possible,” he said. He believes the same will happen in Formula E.

The European Commission played a key role in Formula E’s birth, telling Formula One’s governing body 13 years ago that it wanted the creation of an all-electric racing series to showcase the technology and sustainability. The early racing cars revealed more about the limitations of electric vehicles than the potential, but the roll-call of manufacturers has evolved to include the likes of Nissan, Porsche, Stellantis and McLaren, underlining the pace of change.

Technical development is still tightly controlled to maintain fair competition among teams and critics argue that this inhibits innovation. BMW and Audi have questioned the transfer technology benefits. Some carmakers prefer to use other racing series as a testing bed because of more development freedom. Every class of motor sport now has a form of hybrid power (Formula E is the only big all-electric series). And not racing hasn’t harmed Tesla’s development.

Nevertheless, Barclay said the benefits of Formula E to Jaguar Land Rover, Britain’s biggest carmaker, were undeniable. There were tests on a new-generation semiconductor material in batteries before deciding to use it in future JLR cars. There’s work on refining and re-using oil and lubricants to assess if this is a sustainable solution for road cars.

Formula E was not about sprinkling racing stardust on the Jaguar brand, Barclays insisted. “As the technology opens up to more development, more manufacturers will get involved. We are the most advanced application of vehicle technology in the world, so if manufacturers are not taking advantage of that, they are missing a trick.”

UK ‘back on track’ for battery capacity

There will be no substantial British car industry without huge battery factories to serve electric vehicle production, but investment in so-called gigafactories depends on carmakers choosing to build their electric vehicles in the UK (Russell Hotten writes).

This chicken-and-egg conundrum is being resolved, albeit slowly, according to Stephen Gifford, head of economics at the Faraday Institution, an energy storage research group that brings together universities, companies and officials in the quest to build a battery industry.

Faraday estimates that about 100 gigawatt hours of capacity will be needed by 2030 and 200GWh by 2040. For a long time, especially after the collapse of Britishvolt, the battery company, last year, Britain seemed way behind what was needed to compete. Tesla’s single battery plant in Germany will have a capacity of more than 100GWh. Germany, with its large motor industry, has a dozen gigafactories and France five.

However, Gifford said: “Over the last 12 months it’s been looking a lot more promising. We’re back on track to get 100GWh. This is a very important moment for the UK.”

In February, Tata Group, the Indian owner of Jaguar Land Rover, confirmed plans for a gigafactory in Somerset with capacity for 40GWh. Last year, ASEC, of China, said that it would add 12GWh to an existing smaller facility near Nissan’s factory in Sunderland. EVE Energy, also Chinese, is close to committing to a 20GWh factory near Coventry, with possible expansion to 60GWh.

• Chinese giant set to build UK’s biggest gigafactory

Gigafactories, though, need supply chains — involving lithium, nickel, cobalt, a processing industry and components — and a recycling strategy. “We have been making the case to government and industry that it now needs to look wider than gigafactories,” Gifford said. “Now there’s a pipeline of gigafactories, there’s an opportunity to look at other weaknesses.”

Britain had a strong chemicals sector and was doing world-leading research into power storage, he said. There’s a small UK lithium industry (the vast majority of raw materials come from Africa, South America and Australia) and south Wales is home to Europe’s biggest nickel refinery.

However, China dominates global processing and that worries governments. The Faraday Institution has emphasised the need for “sovereign capabilities” to avoid global political risk. So is there concern that two Chinese companies want to build UK gigafactories? “There would be if that was all that’s happening in the UK,” Gifford. “It’s not.”